Σας παρουσιάζουμε ολόκληρη τη συνέντευξη του πρίγκιπα Νικόλαου στο περιοδικό GQ οπως ακριβώς δημοσιεύτηκε στις 13 Νοεμβρίου:

After 44 years in exile, the enigmatic Greek royal playboy once called the ‘Most Wanted Prince in London’ has returned to a country in turmoil. Here, GQ meets Prince Nikolaos, now a remarkable landscape photographer using art to reconnect with his homeland.

Special thanks to Dylan Jones

Editor of GQ and fashion biannual GQ Style, for this article.

Friday 5 June was something special. This was the day the country was due to make a €300 million (£220m) payment to the International Monetary Fund, and the sense of unease in the city streets was more than tangible.

Not that many people appeared to think the payment would be made, or that any kind of deal would be done. To judge from news reports, as the country’s bailout creditors huddled behind closed doors in yet another attempt to hash out an offer for their beleaguered debtor – drowning in what the European Commission called «paperology» – the mood in the capital was meant to be one of unease and defiance. Yet most people I met in the city appeared to be tired and underwhelmed by the Syriza government’s attempts to salvage the country’s dignity. It was also almost impossible to find anyone to admit to having voted for prime minister Alexis Tsipras. No taxi driver, no shop assistant, no retailer, no restaurateur. No prince, come to that. The percipient opinion of a barman in the Plaka district appeared to be typical: «Everyone here wants to be the master, nobody wants to actually do any work…»

The only believers seemed to be students, and to a person they were raging about the inability of Tsipras to deliver his side of the electoral bargain. Walking in front of the Hellenic Parliament overlooking Syntagma Square («Constitution Square») around 4pm, demonstrators were already putting up their makeshift tents, unfurling their banners, and setting up little tables for their food and beverages. As the demonstrators were mainly undergraduates, the beverages were mainly beer.

Later in the day, instead of appeasing the IMF, Greece decided instead to defer payment, and it soon transpired that, as many had foreseen, the government would be unable to deliver any kind of shortcut out of the country’s economic predicament. Tsipras and Yanis Varoufakis, the then finance minister, would find that the future held little but fiscal retrenchment, tough economic reforms and cheap retsina.

Still, on 5 June, as day slipped into night, the crowds in Syntagma Square were gearing up for another evening of alcohol-fuelled demonstrations, more than happy to indecorously celebrate the antithetical nature of the crisis. A few miles away, in Kastri, a wealthy northern suburb full of modernist apartment blocks and pollarded trees, the previously exiled Prince Nikolaos of Greece and Denmark was also expounding on his country’s profoundly existential problems, albeit in a rather more tempered manner.

«I believe that the government is doing its best in its own way,» he said, with as much diplomacy as possible. A tall, good-looking man, he has rather hooded eyes, which makes his cautiousness more pronounced. «They’ve got a mandate from the people and they’re trying to fulfil that mandate and I sincerely wish them well. I’m not a truthsayer, but I do believe that we will eventually have an agreement. We have to. What form and shape that agreement will take, I cannot tell, but obviously it will happen.

«As you can see, the situation here in Athens is very different from how it has been portrayed in the media. Of course there are a lot of people who are suffering terribly, and some are actually going hungry, but life goes on. It’s not like the whole country has ground to a halt. People are trying to get on with their lives, trying to make a living, trying to meet their tax requirements. It’s not easy, but life goes on.»

Prince Nikolaos

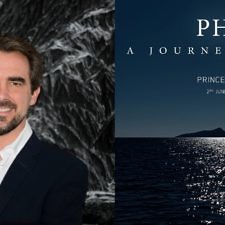

In his modest way, Prince Nikolaos is certainly getting on with his life, having recently moved back to his country to try and forge a career for himself as an artist, a high-end landscape photographer. He has already built up a substantial body of work, has some reliable gallery connections, and is slowly starting to show his pictures publicly. The art world is no less bruising than the world of politics, and its resourcefully cynical custodians don’t suffer fools gladly. So far, however, the prince has only won admirers.

He has had a long journey to this place: the prince is the second son and third child of former King Constantine II of Greece (a first cousin once removed of the Duke of Edinburgh, and Prince William’s godfather) and Anne-Marie of Denmark, the youngest daughter of King Frederick IX of Denmark. He was born in Rome in 1969, due to the coup that ousted the monarchy and caused the royal family to flee to Italy two years earlier. In April 1967, right-wing colonels overthrew the democratically elected government. When King Constantine, then only 26 and on the throne barely three years, unsuccessfully attempted a counter-coup eight months later, his family fled to Italy, finally settling in London, in Hampstead Garden Suburb. Seven years later the government officially abolished the monarchy, and so the entire Greek royal family spent the next 40 years in exile.

Until 2013, that is, when Constantine and Anne-Marie moved back to their crisis-plagued homeland, following a similar move by Nikolaos and his wife Princess Tatiana (a former events planner for the Diane von Furstenberg label, and something of a beauty) shortly before. At the time the king said, «No one can keep me away. For so many years I have lived through my own Golgotha, now I am ready to return.»

For ten years, the monarch waged a campaign to retrieve the various properties that were seized by the socialist Greek government in 1994, when the family were officially stripped of their nationalities and fortune. He eventually won the battle when the European Court of Human Rights ruled that he should be compensated, although the £7m he was awarded was rather less than the £300m he claimed they were worth. These proceedings were one of the reasons the family didn’t move back earlier.

Prince Nikolaos

The final decision to move back to Greece was one, like many in the metaphorical royal household, made by Tatiana. «I was talking with my wife about the possibility of maybe moving here and we came to the conclusion that there was nothing to stop us,» says Nikolaos. «We don’t have children yet, so it wasn’t a question of putting children in new schools or worrying about how they were going to adapt, so we said if we’re going do it, it’s got to be now and I haven’t regretted it at all. Living abroad in quote-unquote ‘exile’, you long for what you can’t have. I was always brought up as a Greek, but there’s one thing to see it on a postcard and another to actually live in the country where you belong. I went to a Greek school with Greeks, and I love the Greek people. Even though I went to a boarding school, I was taught the Greek language, Greek culture, Greek ways of living.»

There was obviously some trepidation – with the salt-lick of bitterness on both sides – although after a while the move became inevitable. «I didn’t know what to expect, but what I was primarily worried about was my wife, whether she was going to enjoy it. It’s one thing to come here in the summers when it’s lovely weather – it’s another to move here for good. She is Venezuelan, raised in Switzerland, and I was asking her to move to a country with a different culture, a different language. She’s adapted incredibly well and she loves it, so you know, I couldn’t have asked for more. I think it was very tough for her in the beginning, particularly as she’s a very private person. She doesn’t like too much attention and to come into a country where you don’t speak the language where everybody recognises you and stares, is not easy.»

I spent two days in Athens with the prince, and on the occasions where we walked around the city, he was greeted with warmth and respect. He doesn’t have security guards, and it would be easy for anyone to accost him, but largely he goes unnoticed; those who do notice him express quiet surprise, or smile and nod. There is strong republican resentment in Athens, yet in the main he seems to have escaped it.

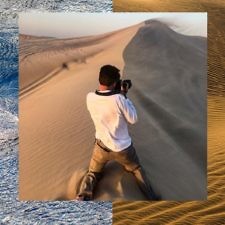

Having moved home, and having re-entered Greek society, a certain amount of reinvention was needed, and the way in which Prince Nikolaos has decided to reinvent himself is as a photographer, a landscape photographer who shoots almost exclusively in colour. What started out as a hobby has now turned into a proper vocation. Nikolaos’ work aspires to the colour photography of Ansel Adams, even though the legendary landscape photographer once likened working in colour to playing an out-of-tune piano. He has been taking pictures since he was a boy, having been given an Olympus OM-10 for a birthday, and was so obsessed that he started collecting filters, lenses, and quite quickly built up a substantial collection. He began to lose interest when digital came in, but it was rekindled a few ago when his wife saw him picking up somebody’s camera and taking pictures like mad and apparently enjoying it. He initially started taking portraits, encouraging his friends to sit for him, but his style was rather uncompromising. «You find out that as people get older, they are not necessarily too happy to see their image represented so accurately where they can see their wrinkles and their blemishes and so on.»

So he began experimenting with landscapes, first on holiday, then with particular projects in mind. «I’ve always liked views and always loved landscapes, but with a few reservations, such as Ansel Adams, I’ve always hated landscape photography. It bored me to distraction. I couldn’t see the whole picture, I was obsessed with people. I’d look at images of trees and mountains and rivers and seas and I wasn’t moved at all, but I changed. I started to realise that if I tried hard enough I might be able to actually capture the beauty of the world. Beauty isn’t all about people.»

He has not just been seduced by the craft of what he does, but by the process too. Halfway through our first interview, he described in great detail – and almost in real time – one particular shoot he did in the very room we were sitting in, describing how he set his camera up and pointed at the swimming pool outside, waiting for gusts of wind to move droplets of water around the surrounding tiles. «Every time the wind blew, the water moved in such a way that it began to resemble exotic leather or crocodile. Like a lot of my pictures, I then spent hours on the computer refining it.»

He uses the Nikon D800 digital SLR – which gives him the resolution he needs to magnify the detail in his pictures – and has started shooting on an iPad. He prints a lot of his material on to aluminium, leaving many of the works outside on the terrace of his apartment, allowing the elements to do their worse. «I’ve left some of my pictures outside for months, just to see what happens to them,» he says. «It’s fascinating what you end up with.»

He is obsessed with composition, and the way in which photographers frame their subjects. This started when he was working in New York for Fox News. «It wasn’t a conscious thing, because I wasn’t a cameraman. I was a production assistant and went out into the field and got stories, but when we were in the editing suite I learned a lot about composition, about framing, editing, and how to get the best from an image or a situation. I was young and I suppose I was paying a lot of attention to the way everything was being filmed.»

Prince Nikolaos

Good landscape photography should reinforce the relationship we have with our surroundings, challenge that relationship, and remind us of the connection we have with the land. It encourages us to appreciate the fragility as well as the strength of nature. Crucially, for the photographer, there is also the challenge of not falling back into cliché. A lot of landscape photography is, by its very nature, melancholy, and while Nikolaos’ photographs are not deliberately desolate, they can quietly infer a sense of mythology. His best work is his simplest, the tricksier pictures looking too keen to impress; the larger, bolder work is the work you’re going to be seeing on gallery walls. Like any sort of photography, landscape photography is an easy thing to do badly, as the clichés are exponential, but Nikolaos avoids almost all of them. This is not easy in a reductive environment in which «extraordinary» images have become the norm; as the New Yorkersaid recently, «the profusion of disembodied digital images has brought photography to the brink of banality», something exacerbated by the success of social platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest. Technology naturally assumes the patina of progress, yet it remains to be seen if this particular narrative succeeds with photography.

If Nikolaos’ photographs convey anything, they convey a reverence for the panoramic beauty of his country – a country that has gifted him a title, but destroyed his heritage. The prince is rebuilding his life in Athens, and as he is unable to involve himself politically, so he is embracing the arts as a way to forge a relationship with his new home.

More importantly, his work appears to have proper resonance, the kind that could turn him into a real success in the art world.

«There’s a clarity to these images in an almost Turner-esque, modern-day manner not like any other seascape photographs I’ve ever seen,» says the influential director of Sotheby’s S:2 gallery, Fru Tholstrup. «There is an extraordinary amount of passion here – possibly because of the childhood that Nikolaos wasn’t able to spend in his homeland, coupled with a sense of relief that he has returned at a time when Greece is now its own Greek tragedy. However, what these images convey is a sense of hope that Greece will begin to heal itself.»

It is perhaps an unlikely career change for the prince. He was educated at the Hellenic College in London, before studying at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. He then joined the British Army, training at Sandhurst before joining the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards as a second lieutenant (where he was known as Nick Constantine). He then worked for Fox News in New York and NatWest Markets in London before running the Anna-Maria Foundation, a charity for disaster victims in Greece. He also briefly worked as a journalist before embarking on an investment career (he is currently involved in the hospitality business). The legendary socialite Taki, a long-time friend of the Greek royal family, says Nikolaos is «Greek in a way we call mangas, which means somebody who is upper class but can mix with anybody. He knows how to behave in Buckingham Palace and the ways of the street.»

In the past it was not his peripatetic career that drew attention from the press, but rather his not-so-private life, as he has enjoyed a reputation as something of a dilettante and playboy. According to one profile, the various soubriquets bequeathed to him included the Best Traditional Greek Dancer In Gstaad, the Most Wanted Prince In London and the Biggest Babe Magnet In Saint-Tropez. It was in London where he gained his reputation as a ladies’ man – walking hand in hand with Elle Macpherson (just friends, apparently), dining with Gwyneth Paltrow (ditto) at Blakes Hotel (where he once kept a suite) and appearing on various eligible bachelor lists in Tatler. He was once described as having the kind of reputation that made former man-about-town Tim Jefferies seem like a Greek Orthodox monk.

He knows that some will view his new-found career with suspicion. Coming from such a public family, and having had such a colourful private life, it would be impossible for him to slip into the art world unnoticed. He knows that there are some who will think that he is just mucking about, looking for something with which to occupy himself.

This is something Nikolaos is acutely aware of. «I am a dreamer, and I don’t feel the need to explain anything to anyone,» he says. «I’m not running for public office. People will make up their own minds about what I do. People are going to appreciate them or not. There is a lot of me in the pictures. I think of them as little spiritual moments. Greece has had all this attention recently, but unfortunately it’s been for the wrong reasons. One of the motivating factors in coming back is wanting to do something positive for the country. I wanted to see if, in my own little way, I could send a positive message about the country. Seeing as I could move back, it seemed ridiculous not to. A lot of people are leaving, and I wanted to make a statement by actually moving here. Who knows, maybe I’ll encourage other people to do the same thing.

«When we decided to move, a lot of people said, ‘Are you crazy?’ ‘Is it dangerous?’ ‘Aren’t you worried?’ That sort of thing. What I tried to explain to them is that obviously you only see what is sensationally newsworthy, like the clashes in Constitution Square. Five streets away, it’s perfectly calm and up here, where I live, it’s perfectly calm. Focusing on the images you get from the news doesn’t give you an accurate picture of what’s going on in the country, so again, I was trying hopefully to motivate some Greeks, like myself, who live abroad, and say to them, you know, it’s not so bad to come back.»

His pictures, abstract though they are, appear to convey a similar message.

Prince Nikolaos

«Being a complete Grecophile myself and having spent every summer there since I was a young child, when I first saw these pictures I was immediately transported back to Greece,» says Fru Tholstrup. «These pictures work.»

So what, if anything, does Nikolaos think this work says about Greece?

«These pictures are all about my Greece,» says the former playboy, his eyes full of expectation. «I love the light here, I love the sky, and I love the earth. The landscapes here in Greece are my favourite landscapes in the world. I wanted my first pictures to be deliberately abstract although I wanted to give a sense of the country. I find Greece is a very passionate and romantic place and I see myself as a very passionate and romantic person.»

Edited by Andreas Megos

http://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It